Father and son: ‘… exceptional talent and originality…’

While the ceramics of father (Merric Boyd, 1888–1959) and son (Arthur Boyd, 1920–1999) are very different, many of the same attitudes and approaches to art influenced both. As members of a notably creative family, both had exceptional talent and originality as artists. It was expected of the children of both Merric’s and Arthur’s generations that they would explore creative ideas and have compassion and respect for others. Known mainly as a potter, Merric was also a sculptor and drew and painted constantly on the themes that inspired his pots. Arthur was primarily a painter but pursued with equal passion the themes of his work in ceramics, drawings and prints.

For both father and son, art was a response to experience and reflection, for interpretation and expression — as well as a means of livelihood. Both touched on other careers but in each case returned to art as a lifelong pursuit. In 1989, Arthur said of his father:

He felt very strongly that pottery ought not to be private, expensive, or special in the exclusive sense … If you had a particular talent or bent, and you were able to organise it into creative effort that could serve others, then you should do that. [1]

Each artist had strong convictions about both work and life to which they held firmly, but each also demonstrated frailty. The support of their wives, Doris Gough (1888–1960) and Yvonne Lennie (b.1920), was crucial; both artists themselves, they also became the family and business managers. Merric could sometimes be unpredictable, but was also charming and inventive, with a sense of fun, making up names for pets and children. He also suffered from epilepsy and for much of his life no medication was available.

As they grew older his children could help him, and Doris, deal with his condition, but at first they were aware of his fits without understanding what they meant. As a child, Arthur was shy, a poor scholar and teased at school, although he always came top in art and in his later work was clearly conversant with wide references to art and literature. As Tom Rosenthal noted of Arthur in 1986, ‘Boyd is a diffident, indeed occasionally faintly inarticulate speaker, but let the patronizing beware. Behind that shy and gentle surface is an “alpha plus” mind.’[2] And Alan McCulloch adds:

Arthur Boyd is a dreamer but he is also a maker of exceptional skill and versatility. He can build a house, fix a car, or make music out of a tin whistle — not to mention drawing, painting, etching and ceramic sculpture. [3]

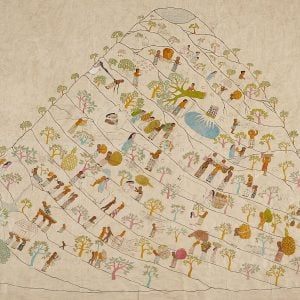

Both Merric and Arthur were introspective and passionate, as well as generous; scholars have variously described the work of both as seeking love, while often expressing isolation or exclusion. Merric closely documented his family, animals, neighbouring people and the landscape around him, while Arthur combined his own accumulated experiences of this environment, and the example of his father, with metaphoric connections and allusions to biblical stories, and myths and allegories in literature and art.

Merric’s spiritual beliefs are evident in the phrases written on many of his later drawings, and although Arthur did not claim a religious conviction, throughout his career he drew on the parables that had been read to him as he was growing up, amongst other stories from the classics. Although pacifists, both father and son nevertheless experienced non-combative war service, Merric in the First World War and Arthur in the second. They were also affected by its social aftermath: Arthur integrated his responses to it into his paintings, while Bernard smith suggests that perhaps, for Merric, ‘the pursuit of art became a personal defence against the innate savagery of humankind.’ [4]

Footnotes

1 Victoria Hammond, Merric Boyd, Studio Potter, 1888–1959, national Gallery of Victoria,

Melbourne, 1990, p 9

2 T.G. Rosenthal, ‘Introduction’, in Ursula Hoff, The Art of Arthur Boyd, AndreDeutsch, London,

1986, p 13

3 Alan McCulloch, in Barry Pearce, Arthur Boyd retrospective, Beagle Press/ Art Gallery of new

south Wales, Sydney, 1993, p 9

4 Bernard smith, preface to Christopher Tadgell, Merric Boyd drawings, Secker and Warburg,

London, 1975, un-numbered [p 3]